Geology

The Geology of Loch Ewe

Our thanks are due to Peter Maguire, Professor of Geophysics, Department of Geology,

University of Leicester, for this article

Introduction

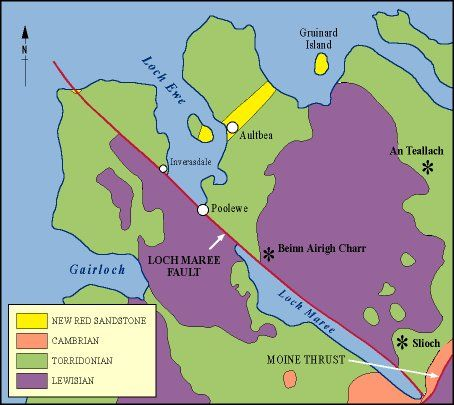

Stand in front of Inverasdale School and gaze over Loch Ewe to the hills. Far to the south, Beinn Eighe gleams white in the sun. Behind Poolewe rises Beinn Airigh Charr, its north facing scarp heading back to Fionn Loch and the towering A`Maighdean, a “cliff girt bastion, which is one of the most spectacular viewpoints in Britain” (The Munros (1985) ed. D.Bennet, Scottish Mountaineering Trust). To the north the buttressed peaks of An Teallach dominate the skyline. In front of these mountains, the shore is ringed by low, levelled hills, like those to the north-east beyond Aultbea, to the south-east sheltering Loch Tournaig, and to the south-west behind Inverasdale protecting the village from south-westerly storms. What is the geological history of this place? What has caused the mountains and hills, the glens and cliffs, the different rock-types that form “Loch Ewe”?

Lewisian Basement

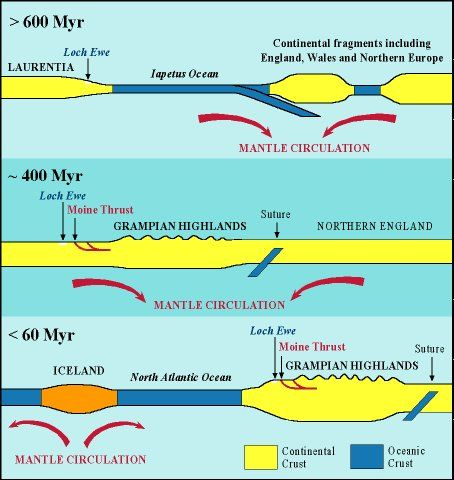

Our Earth is 4500 million years old. The oldest rocks that can be seen from our viewpoint are over half that age, being some of the oldest rocks on Earth. They form the Lewisian complex and originated some 20km deep within the Earth`s crust between 2900 and 1800 Myr ago. They were part of a major continental landmass, “Laurentia” including present Greenland and North America. Lewisian gneiss is a metamorphic rock, generally consisting of light and dark bands, grey-green in colour and formed under high pressures and temperatures. Here these rocks are intensely deformed and constitute the basement to all the other geological rock-types that can be seen. Grey-green boulders of Lewisian gneiss can be found on the shorelines, eroded off the hills, heavy, and rounded by the action of the sea. The long ridge between Poolewe and Inverasdale on the west side of Loch Ewe is formed of these rocks. In places they can be seen to be cut by black Scourie “dykes”, dark volcanic magma that forced its way up near vertical cracks to the surface during a period of crustal extension between 2400 and 2000 Myr ago. It was during this period that major north-west to south-east trending faults were formed as shear zones deep in the crust, now so well defined by the straight north-eastern shore of Loch Maree, and the scarp on the north-facing side of Beinn Airigh Charr.

Torridonian Sandstone

About 1000 Myr ago titanic earth movements, resulting almost certainly from the collision of continents throwing up great mountain ranges as those of the Himalaya today, caused massive uplift of the Lewisian basement. Later these mountain ranges collapsed under gravitational forces generating extensional basins into which are deposited massive sequences of sedimentary rocks.

Sediments derived from a mountainous area undergoing severe erosion to the north-west of Loch Ewe, buried the Lewisian landscape, itself with at least 600m of topographic relief, in huge thicknesses of dark red sandstone deposited into basins by vast braided river systems flowing from the mountains. These are the Torridonian sandstones, flat-lying strata forming the characteristic massifs of An Teallach, of Slioch, as well as the lower lying regions around the northern parts of Loch Ewe.

Cambrian Quartzite

After deposition of the Torridonian sandstones, some 400 Myr passed with erosion producing a flat-lying surface of sandstone and gneiss on which Cambrian sediments were deposited as the sea encroached over the gently subsiding margin on the south-eastern side of Laurentia, the region now forming the continental shelf. To the south lay a vast, but closing ocean, Iapetus, and further south still, the advancing fragmented landmass of what is now England, Wales and northern Europe. These Cambrian sediments, sandstones, form the hard white quartzites found on the top of Beinn Eighe. They contain trace fossils of organisms which lived in the sand in small vertical tubes or burrows. These can be seen in the “pipe-rock”, outcrops of which may be seen high up on the Mountain Trail in the Beinn Eighe Nature Reserve.

The Caledonian Orogeny

The closure of Iapetus between 450 and 400 Myr, the climax of the Caledonian Orogeny, raised great mountains in Scotland, the Grampian Highlands. The suture line between the two continents on either side of Iapetus lies beneath the Scottish Borders. In the north of Scotland, rafts of surface rocks were thrust north-westwards over the Laurentian foreland, the frontal Moine thrust reaching to Glen Docherty at the south-east end of Loch Maree. The region along the coast, including Loch Ewe was relatively unaffected by these Caledonian earth-movements.

New Red Sandstone

Around Loch Ewe there is a notable sequence of later 250 Myr old lighter purpley-red sandstone rocks to be seen at Camus Mor near Rubha Reidh, and also in a thin strip from Aultbea to Laide. These are New Red Sandstone rocks, thinly interbedded, pebbly sandstones and conglomerates, derived from local uplands to the south and laid down in alluvial fans, washed out from the ends of river systems from the hills.

The Opening of the Atlantic

Some 60 Myr ago the huge Tertiary volcanic centres of Rhum, Ardnamurchan, Skye, Mull and Arran were emplaced in the crust. Vast outpourings of basaltic magma occurred as Northwest Europe split from Greenland forming the North Atlantic Ocean in between. Loch Ewe and its surrounds were passively responding to the splitting of the continents and remained relatively unaffected by this massive volcanic activity not so far to the south.

Glaciations

Following the cessation of volcanic activity about 50 Myr ago, the region suffered uplift after which the major scenery forming event of the Glaciations began about 1.8 Myr ago to the end of the Great Ice Age some 10,000 years ago. We have a lot to thank the Ice Age for in the grandeur of the hills!

The landforms produced by this glaciation are well-known: U-shaped valleys as seen in Glen Docherty; glacial striations (lines) on rock faces, where rock fragments and boulders have been dragged over the surface by the ice; and the deposition of moraines at the snouts and sides of glaciers as they melt and retreat, classically seen in the Coire a`Chaud-Chnoic (the corrie of a hundred hillocks) opposite Beinn Eighe on the Kinlochewe to Torridon road.

Earthquakes

The region has a long history of earthquake activity, one of the earliest recorded events being in 1597 when tremors were reported from Ross and Cromarty to Perth. Recent monitoring by the British Geological Survey has recorded a number of small local events, one of the most recent in the Fionn Loch region beneath Beinn Airigh Charr, which was felt throughout the area.

Conclusions

The region is a visitor`s and walker`s paradise. To be aware of the history of the rocks that form the mountains and glens, brings us closer to the landscape on which we live. Go to the hills or beach, pick up and read these rocks which have `lived` for millions of years, seen continents collide, mountain ranges form and the creation of oceans. There is a lifetime of study beneath your feet.

Article © Peter Maguire, University of Leicester.

Reference List

For further information the following will be of interest:

- “The Highland Geology Trail” by John L.Roberts, published by Luath Press. Available from Amazon UK and Amazon.com

- The Northern Highlands of Scotland by G.S.Johnstone and W.Mykura, published by the British Geological Survey.

- The Late Precambrian Geology of the Scottish Highlands and Islands by M.S.Hambury, I.J.Fairchild, B.W.Glover, A.D.Stewart, J.E.Treagus and J.A.Winchester. Geologists` Association Guide No. 44, published by the Geologists` Association.

- Scotland – the Creation of its Natural Landscape by A.McKirdy and R.Crofts, published by Scottish Natural Heritage and the British Geological Survey

- Geological map of Gairloch, Scotland Sheet 91 and part of sheet 100, published by the British Geological Survey.

- “Pocket Guide to Rocks and Minerals” by D.Cook and W.Kirk, published by Larousse.